#l: sanskrit

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Page 113 from Kalāpustaka (MS Add. 864)

#manuscript#illuminated manuscript#ms add. 864#kalāpustaka#bhagavata purana#mahābhārata#rāmāyana#vetālapañcaviṃśati#jātaka#c: nepalese#y: 1600s#l: sanskrit#t: page

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

HOW sexy is it that Russian голод (gólod; "hunger") is cognate with Sanskrit गृध्र (gṛ́dhra, “desiring greedily”) and why is it 1375927/10

#. help me. i'm down That rabbit hole again#. it being wiktionary#. godddd#russian#sanskrit#langblr#etymology#l#r.txt

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

[ID: A Moroccan teaglass with a bundle of sage, a saucer of dried sage, a deep blue-purple teapot, and a Palestinian vase in the background. End ID]

شاي المريمية / Shay al-maryamiyya (Palestinian sage tea)

Palestinian sage is a common after-dinner beverage and digestive aid made from black tea and three-lobed wild sage (Salvia fruticosa syn. Salvia triloba L.). In the Levant, this variety of sage is known as "مَرْيَمِيَّة" ("maryamīyya") or, more dialectically, "مَرْمَرِيَّة" ("marmariyya").

Terminology and etymology

The term "maryamīyya" likely derives from the Aramaic "מרייא" ("marvā"), meaning "common sage" (Salvia officinalis). The modern form of the word in Arabic—as well as in Persian, in which "مریم گلی" ("maryam goli") is “sage” or "garden sage"—was also influenced by a folkloric association between sage and the مَرْيَم (Maryam) of the Bible (Mary, mother of Jesus). Dr. Tawfiq Kanaan, for example, says that Mary sat on a stone to rest after a walk in the hot summer sun, and used a few leaves from a sage plant to dry her forehead: this is how the plant got its pleasant scent, and why it is still named after Mary. The dialectical pronunciation "marmariyya" then arises through an assimilation of the second syllable to the first.

"Maryamīyya" is perhaps also related to the obsolete Arabic مَرْو ("marw"), meaning "fragrant herbs" [1]. This Arabic term is derived from the Aramaic מַרְוָא / ܡܲܪܘܵܐ ("marwā"), which refers to wild marjoram or za'tar (Origanum syriacum; syn. Origanum maru) and is related to words for fragrant herbage, marjoram, and grass (Ciancaglini; see also Aramäische Pflanzennamen, p. 193). The Aramaic is itself a borrowing from the southwest Middle Persian "𐭬𐭫𐭥𐭠" (transliterated: mlw'; pronounced /marw/) [2], which survives in several New Persian words: see for example "مرغ" ("margh"), "a species of grass of which animals are exceedingly fond"; and "مرو" ("marv"), "a fragrant herb." (Interestingly, the related Sanskrit मरुव "maruva" ultimately gives the English "marjoram" by way of Latin and Old French.)

[1] The term may also refer to the genus Maerua (to which it gives its name), and in particular the species Maerua crassifolia.

[2] See also Müller-Kessler, p. 10, and note 41 on p. 29; MacKenzie, p. 55.

Sage and Palestinian Culture

Three-lobed sage is one of the "most deeply rooted plants in the Palestinian traditional culture and ethnobotany," being the second-most-mentioned of all foraged plants (after za'tar) in a survey conducted in 2008. The connection of three-lobed sage to Maryam leads to its use in creating protective blessings at various rituals from birth until death; in the Galilee, it is burned to guard against the evil eye and to expel demons at births, weddings, and at the graves of holy people. When consumed, it is believed to help with many ailments including stomach complaints, eye diseases, and insomnia, and is used to treat livestock as well as humans.

Maryamiyya is not commonly grown as a garden herb in Palestine; rather, it is foraged from its wild range across the mountains of the West Bank, where it scents the air. Like za'atar and labna, using maryamiyya for culinary purposes is connected to Palestinian identity throughout all regions, with some people asserting that every Palestinian household must have some in stock.

Tea made with the addition of sage is perhaps the most popular herbal tea in Palestine, especially in the winter: though mint, chamomile, and aniseed are also commonly infused in water and drunk. Other varieties of sage grow in Palestine and are produced and exported by Palestinian farmers [1], but Gustaf Dalman noted in the early 20th century that three-lobed sage was the most important variety:

Of the spicy-smelling labiate flowers, which assume a significant role in the flora of Palestine, numerous sage varieties bloom in the spring. Among these the Salvia triloba, with violet flower heads on a tall shrub, is not the most colorful but is the best known, called in the north 'ēzaqān [عِيزَقَانْ] and in the south miryamīye, mēramīye thus connecting it with the Virgin Mary. (trans. Nadia Abdulhadi Sukhtian)

During the spring, sage leaves are collected and air-dried for use in tea throughout the whole year. Tea may also be made from fresh leaves, but some people consider dried to be superior. Dried maryamiyya leaves are purchased by Palestinian refugees and expatriates wherever they are. Food is thus tied to locality, memory, resistance, and terroir—a groundedness in land that considers aspects as diverse and interconnected as soil, climate, and politics. A concept of terroir in agriculture and cooking brings out how products "register[] origin and provenance."

[1] Today, the vast majority of Palestinian herb exports are to the United States, but Palestinian farmers are not able to export goods themselves—they rely on Israeli distributors and exporters, which cuts into their profits and curtails their autonomy.

Criminalizing Foraging

Ali-Shtayeh et al. noted in 2008 that the gathering of wild edible plants had been in decline in the Palestinian territories throughout preceding decades, with many young people lacking the cultural knowledge to identify and prepare wild plants. They mention several possible reasons for the decline, including an increase in intensive agriculture, improvement in national networks of roads, and the fact that some middle-aged people associate foraging with times of poverty. But we should also consider the fines, arrests, and potential imprisonment that Palestinians risk when foraging wild plants for food as a likely cause for the decline in the practice.

There are two strains of law relevant to the criminalization of foraging in "Israel" and the occupied Palestinian territories (the West Bank and Gaza: henceforth "OPT"). The first consists of primary laws which establish the right of representatives of the Israeli government to declare a plant to be a protected "natural value" (ערכי טבע), and lay out the maximum penalties people can be charged with for causing "harm" ("פג'עה") to a protected plant; the second comprises secondary declarations in the form of lists of which plants are considered protected.

The 1963 Natural Parks and Nature Reserve Law (חוק גנים לאומיים ושמורות טבע, תשכ"ג - 1963) belongs to the first strain. It empowered the Minister of Agriculture to declare a plant to be protected within "Israel," subject to the approval of a government council (ch. 5, 40-42); and declared that harming a plant was an offence punishable by up to three months' imprisonment (chapter 6).

In the text of the law, "harm" is specifically defined to include "picking," "קטיפה," and "gathering," "נטילה." No systematic distinction is established based on how much of the plant was harvested, and whether the plant was foraged for personal or commercial purposes. Nor is there any qualification of what qualities a plant should have to be considered "protected," or any obligation for the government to pursue or present scientific evidence that a given plant is overharvested.

In 1969, The Decree on the Protection of Nature (צו בדבר הגנה על הטבע) (Military Order no. 363) gave similar authority to the occupying military, and criminalized foraging in the OPT. Military orders are enforced by military courts, whereas offenders in "Israel" go through civil courts.

Several plants were already on the list of protected natural values at this time, but they were not commonly foraged for food. 1977 proved a signal year in this regard: with the "Proclamation of National Parks and Nature Reserves" [אכרזת גנים לאומיים ושמורות טבע (ערבי טבע י מוגנים), תשל״ח -1977], Minister of Agriculture Ariel Sharon (אריאל שרון) added za’tar ("אזוב מצוי") and maryamiyya ("מרוה משולשת") to the list. The inclusion of these plants, and especially za'tar, was more disastrous and insulting than previous bans on foraging had been. Za'tar, besides being a source of food and income for many poor or disabled Palestinians, has immense cultural significance in Palestine.

Arab Palestinians—and only Arabs—were arrested, fined, and even imprisoned, with no clear correspondence between the amount they had foraged and their sentencing. Most of the recorded court cases in "Israel" deal with za'tar, though court cases in legal databases show that Palestinians were also fined and tried for foraging maryamiyya (FN 38). An atmosphere of intimidation prevailed, with many habitual foragers feeling newly afraid to leave their homes.

In 1998, a new National Parks, Natural Reserves, National Sites and Memorial Sites Law [חוק גנים לאומיים, שמורות טבע, אתרים לאומיים ואתרי הנצחה, תשנ"ח-1998] replaced the prior National Parks law (of 1992, which had itself replaced the aforementioned 1963 law). It removed the necessity for an ecological council to approve the Minister's declaration of a "protected" status, and increaed the maximum prison time for a violation of the law to three years. Throughout all periods, however, the penalty usually imposed has been a fine.

Since the imposition of the harsher law, two notable updates have been made to the list of protected plants: the 2005 list of Protected Natural Assets) [אכרזת גנים לאומיים, שמורות טבע, אתרים לאומיים ואתרי הנצחה (ערכי טבע מוגנים), התשס״ה–2005] replaced the 1979 list, and added عَكُوب ('akoub; "עכובית הגלגל"), a culturally important and commonly foraged thistle. [1] Za'tar and maryamiyya remained on the list. The 2005 declaration also specifies that the species on the list are protected if they are wild, but not if they are cultivated (section 3). This provision allows Israeli farmers to profit from the farming and sale of za'tar.

The second notable update came in 2019: the Nature and Parks Authority (שרשות הטבע והגנים) announced that it would redact the absolute ban on harvesting za'tar, maramiyya, and 'akoub, instead setting a maximum allowable amount for household consumption and cracking down on the sale of these plants, rather than on foraging itself.

Activists believe this partial measure to have occurred as a result of legal and public pressure instigated by an open letter which human rights lawyer Rabea Eghbariah sent the Israeli Attorney General and Environmental Protection Minister requesting that za'tar, 'akkoub, and maryamiyya be removed from the "protected" list in advance of their foraging seasons, noting the inconsistency in sentencing and the law's disproportionate criminalization of Palestinians. (The specific cultural importance of these three plants is attested by the fact that they, among the dozens of species considered "protected," form the basis of Eghbariah's complaint.) The Nature and Parks Authority (NPA), however, insisted that an independent assessment, and not public criticism, had led them to announce the change in policy. And fines levied at Palestinian foragers did continue despite the announced change in policy, at least through March 2020.

Nor is the change complete in scope, even if it were being upheld. Eghbariah notes that "It is not yet clear if the change will also apply [in the West Bank] - and there it is a parallel system, less transparent and much more predatory. The enforcement is much worse, including the confiscation of cars, and the judgment is in a military court. We will continue to monitor."

[1] Eghbariah writes that the "Protected Natural Values Declaration (Amendment No. 2) (Judea and Samaria), 1978" added za'tar and maramiyya to the list in the OPT, and the "Protected Natural Values Declaration (Amendment No. 2) (Judea and Samaria), 2004" added 'akoub. I have been unable to find or independently verify the text of either declaration. From a list of secondary legislation related to military orders, I believe the declaration being amended is "הכרזה בדבר ערכי טבע מוגנים (יהודה והשומרון), התשל"ג - 1973".

[ID: Light shone through a blue glass vase is cast over the bundle of sage and glass of tea. End ID]

"Preservation" and Green Colonialism

Of course, Palestinians and activists also suspect that the underlying purpose of the ban is to starve and intimidate Palestinians, rather than any real concern with nature. Israeli botanist Nativ Dudai points out that foraging causes much less harm to these plants than Israeli bulldozers do. Samir Naamneh, who sells foraged produce, also dismisses the environmentalist excuse for the ban on foraging:

We feel, and we know, and we’re sure, that the laws are made, on principle, against the Arab residents of the country, to hurt their livelihoods. It’s part of the pressure that Israel puts on us to starve us out.

The 1977 decision to add za'tar and maryamiyya to the protected plants list was ostensibly taken in accordance with a report submitted by a group of Israeli ecologists, which suggested that the species were in danger due to over-foraging. However, Israeli forager Yatir Sade (יתיר שדה) suggests that the converse may be true, and that the people who wrote the report might have taken their cues from the government.

On June 20, 1977, the inauguration of the Begin (בגין) Cabinet marked the first time that a right-wing party had held a majority in the Knesset; this dramatic change in Israeli politics would come to be called "המהפך" ("HaMahapakh"), "the revolution" or "the upheaval."

Sade's research reveals that, about a week later, on June 27, 1977, a team of ecologists at the NPA submitted a list of species to the Legal Bureau at the Ministry of Agriculture (משרד החקלאות), suggesting that they be declared protected. The list is accompanied by a letter of legal advice signed by a partner in the law firm Reva, Shein, Katz & Co. This initial suggested list did not include four species which would end up on the final 1977 list, all of them important culinary and medicinal herbs among Palestinians and Bedouin Arabs: babonj (בבונג / بابونج / golden chamomile), maryamiyya, za'tar, and ss'atr barriyy (صعتر بري / קורנית מקורקפת / Persian hyssop). [1]

But about four months later, on October 16, another letter was sent on behalf of the same law firm, requesting that these four species be added to the "protected" list, and that the standard procedure for adding them be expedited. Accordingly, on November 2, only a few days after receiving the letter, the Minister's office published the final declaration, with golden chamomile, maryamiyya, za'tar, and Persian hyssop newly added. The new Minister of Agriculture Ariel Sharon (אריאל שרון), part of the First Begin Cabinet and co-founder, with Menachem Begin, of the right-wing party HaLikud (הליכוד), signed the new declaration. It therefore seems likely that these plants were added to the list for political reasons and precisely because of their importance to Palestinian Arabs, rather than from any ecological concern.

It is also relevant that the 1963 and 1998 laws which criminalized foraging also laid out guidelines for the creation of national parks, nature reserves, and military and state memorial land. The text of the 1998 law, in particular, describes the goals behind creating these sites, and gives the council it establishes the authority to do anything necessary to promote those goals. These goals include to "protect natural and heritage sites" ("הגן על ערכי הטבע והמורשת"); to "maintain international scientific relations" in the field of nature conservation ("קיים קשרים מדעיים בין-לאומיים") ; to promote education about conservation among youth and students (7. (א)); and to promote travel and tourism (14. (א)).

Many discourses and strategies can here be seen operating together. The creation of nature reserves, state heritage sites, and military memorial land all within the text of the same law explicitly connects environmentalism to patriotism; creates special reasons for bringing land under state control, and imposing special codes of behavior on this land (i.e., natural and heritage sites); connects environmentalism to state ownership and control of land, and connects both to the education of youth and the creation of the ideal Israeli civic subject; uses environmentalism to promote Israel internationally as a scientific authority, a responsible steward of land (unlike the indigenous population), and thus a legitimate state; and sanitizes and 'advertizes' Israel internationally by associating sites of destruction, annexation, and ethnic cleansing with the concepts of environmental protection, natural beauty, preservation, and heritage.

Israel frequently declares land a "nature reserve" as a method of annexation, only to later build settlements on it (see Karimi-Schmidt p. 369 ff). Palestinians are forbidden from foraging certain plants within nature reserves (other plants are forbidden for foraging everywhere), and from constructing on them; they are thus alienated from this land, and dissociated from the ways in which they have long related to it. Yatir Sade points out that the four plants added to the original 1977 draft of the protected species list are typically harvested out in open areas, rather than within yards and villages; declaring these areas nature reserves, or arresting Arabs who enter them under suspicion of foraging, prevents Palestinians from moving freely, and from claiming any connection to the land. [3]

The "Green Patrol" (HaSayeret HaYeruka / הסיירת הירוקה), the enforcement unit for the NPA, was founded in 1976 by then-Minister of Agriculture Aharon Ozan and director of the Israel Land Administration Meir Zore, for the specific purpose of policing "open areas" (שטחים פתוחים) which had been declared state land, and preventing Palestinians from "tresspassing" ("הסגות גבול") or illegally building in these areas. [4] Through these strategies, land is appropriated for the state's and settlers' purposes under the guise of environmentalism.

In much the same way, the list of protected species is ultimately about using environmental science to cement state authority. Irus Braverman points out that endangered species lists function as a means of regulation, not least by being ostensibly objective: "their global power, mobility, and ubiquity derive from their configuration as scientific, technical, and quantitative, and therefore as neutral and apolitical." The protected species list thus joins other "environmental infrastructures," such as renewable energy and agricultural technologies, as a "mechanism[] for land appropriation and dispossession" of the indigenous population: together, these infrastructures make up a strategy that is alternately called greenwashing, green grabbing, and green colonialism.

[1] Letter regarding the declaration of national parks and nature reserves (protected natural values), 1977, from Ofir Katz to Tovi R. [מכתב בנושא אכרזת גנים לאומיים ושמורות טבע (ערכי טבע מוגנים) תשל"ז-1977, מאופיר כץ לטובי ר'], 6/27/1977. In: Proclamation of National Parks and Nature Reserves (Protected Natural Values), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development [אכרזת גנים לאומיים ושמורות טבע (ערכי טבע מוגנים), משרד החקלאות ופיתוח הכפר], January 1965–October 1982. State Archives, ISA-moag-moag-00119qy, pp. 164-175.

[2] Letter regarding a proposal to declare national parks and nature reserves (protected natural values), 1977, from Ofir Katz to Tovi R., [מכתב בנושא הצעה לאכרזת גנים לאומיים ושמורות טבע (ערכי טבע מוגנים) תשל"ז-1977] 10/24/1977. In: Proclamation of National Parks and Nature Reserves (Protected Natural Values), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, January 1965–October 1982. State Archives, ISA-moag-moag-00119qy, p. 160.

[3] Yatir Sade, Master's thesis, pp. 68-9. Personal communication.

[4] Sade points out that Yehuda Reva (יהודה רווה), another partner of the law firm that provided legal advice on the matter of the 1977 protected species list, was also prominent in helping the Green Patrol expropriate Palestinian land and property within the bounds of Israeli law (Master's thesis, p. 44, FN 34).

Foraging and Food Sovereignty

The disastrous effect of these strategies and regulations should not be understated—but nor should their power to control Palestinians' behavior be overstated. Palestinians reference specific plants in writing and in art (including ceramics and tatreez), bring dried herbs to family members abroad, purchase or grow important culinary plants wherever they live in the diaspora, and continue to forage plants despite harassment and the risk of fines and arrest. Plants are an important way of symbolizing, and of practicing, resistance, resilience, and rootedness in history and in the land.

Foraging can be a strategy of reconnection in defiance of dispossession. Rochelle Davis notes that Palestinians often visit the villages from which they were displaced in order to gather grape leaves and herbs, “ingesting the place by consuming the land’s produce” (p. 172). Through this practice, as Anne Meneley puts it, "[e]ating becomes an act of momentary repossession."

The message boards on PalestineRemembered.com attest to this practice. When Mouttaz Ammoura returned to الطيرة (Al-Tira), the village from which his family was displaced, he noted maramiyya as the one plant he brought back with him:

Now I live in Canada, but far-away from AL-TIRA. When I came back, I brought with me some sand, maramieh, few stones, & water from Tirat Haifa. Yes, I brought all of that to remember al-Tira & to have it close to my hart back in Canada.

In an interview conducted in a Palestinian refugee camp in 1998, women demonstrate this same association of plant life with place:

They spoke of the names of land plots around ~ Tjzim (Wadi al-Nahel, Durat al-Qamar, Shana), and the act of naming evoked an aura of magic for those who remembered the places [...]. They also related to the wild plants. The women, who felt we had shifted to familiar ground, called out the names — khubeize (mallow), ‘aqub (tumble thistle), maramiyyeh (sage), za’atar (thyme).

Mirna Bamieh's Palestine Hosting Society put on an Edible Wild Plants Table, which registered the connection of foraging to place, local knowledge, and temporality. The project, which focused on "identifying the names, forms, locations and availability of wild plants in Palestine’s nature," involved a menu created from foraging in the mountainous regions of Palestine during the blooming season "from mid-January until the end of February."

Foraging is also one strategy among many that Palestinians use—alongside instituting agricultural innovations, creating native seed banks, educating about Palestinian cuisine, and seeking out contracts with foreign markets—to attain food self-sufficiency and sovereignty. It is therefore both a symbolically defiant strategy, and a practical one. Palestinians illustrate a belief in the illegitimacy of Israel's laws and claims, and insist on the primacy of their relationship to the land, when they forage for food.

When asked whether he believed that 2020 would bring the promised relaxation in criminalization of foragers, Samir Naamneh, who has been repeatedly fined, arrested, and tried over the past decades, told Dror Foyer (דרור פויר):

"We'll live and see, but it won't change anything for me: whether it's allowed or not, I'm going to forage. I do the work I love, and I'm at peace with myself. The fact that I'm making a statement to the State of Israel and their law—that's enough for me."

Donate to an evacuation fund

Donate eSims

Palestinian heirloom seeds

Ingredients:

250g filtered water

2.5g (1 1/2 tsp) high-quality loose leaf black tea

4g (1 1/2 Tbsp) dried three-lobed sage, or substitute another variety of sage

Sugar, to taste (optional)

Dried three-lobed sage can be purchased from a Palestinian brand such as Al-'Ard or Yaffa (not "Jaffa").

Instructions:

1. Combine tea with just-boiled water and steep for two minutes.

2. Add sage and steep for another minute.

3. Pour into tea glasses and serve hot.

Times and quantities are geared towards producing a tea that is mild enough to be enjoyed without sugar. Adjust as per preference.

371 notes

·

View notes

Text

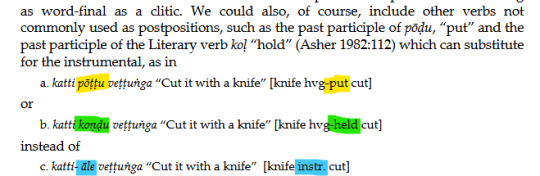

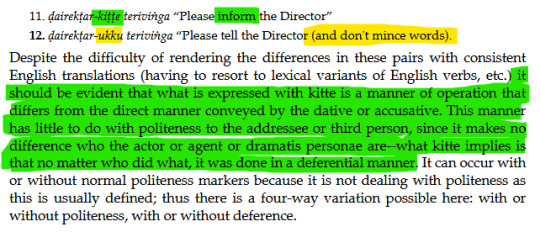

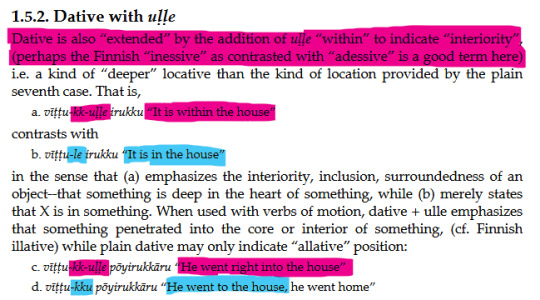

Tamil Linguistics thread (bc nobody cares but me)

but really, if you are interested in linguistics at all, give this post a read, because this shit really blew my mind ...

have been reading the following paper: https://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~haroldfs/public/h_sch_9a.pdf

"The Tamil Case System" (2003) written by Harold F. Schiffman, Professor Emeritus of Dravidian Linguistics and Culture, University of Pennsylvania

Tamil is one of the oldest continuously-spoken languages in the world, dating back to at least 500 BCE, with nearly 80 million native speakers in South India and elsewhere, and possessed of several interesting characteristics:

a non-Indo-European language family (the Dravidian languages, which include other languages in South India - Malayalam being the most closely related major language - and one in Pakistan)

through the above, speculative ties to the Indus Valley Civilization, one of the first major human civilizations (you can read more about that here)

an agglutinative language, similar to German and others (so while German has Unabhängigkeitserklärungen, and Finnish has istahtaisinkohankaan, in Tamil you can say pōkamuṭiyātavarkaḷukkāka - "for the sake of those who cannot go")

an exclusively head-final language, like Japanese - the main element of a sentence always coming at the end.

a high degree of diglossia between its spoken variant (ST) and formal/literary variant (LT)

cool retroflex consonants (including the retroflex plosives ʈ and ɖ) and a variety of liquid consonants (three L's, two R's)

and a complex case system, similar to Latin, Finnish, or Russian. German has 4 cases, Russian has at least 6, Latin has 6-7, Finnish has 15, and Tamil has... well, that's the focus of Dr. Schiffman's paper.

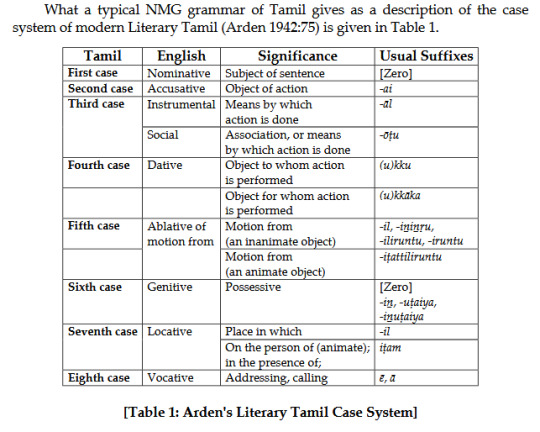

per most scholars, Tamil has 7-8 cases - coincidentally the same number as Sanskrit. The French wikipedia page for "Tamoul" has 7:

Dr. Schiffman quotes another scholar (Arden 1942) giving 8 cases for modern LT, as in common in "native and missionary grammars", i.e. those written by native Tamil speakers or Christian missionaries. It's the list from above, plus the Vocative case (which is used to address people, think of the KJV Bible's O ye of little faith! for an English vocative)

... but hold on, the English wiki for "Tamil grammar" has 10 cases:

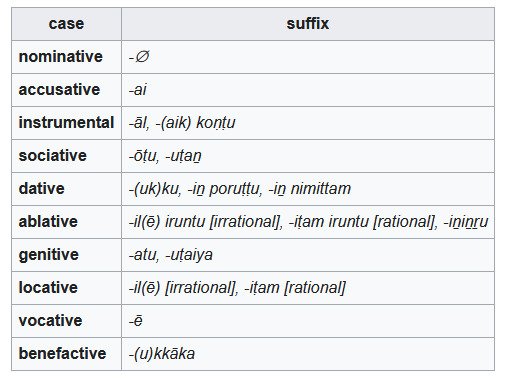

OK, so each page adds a few more. But hold on, why are there multiple suffix entries for each case? Why would you use -otu vs. -utan, or -il vs -ininru vs -ilirintu? How many cases are there actually?

Dr. Schiffman explains why it isn't that easy:

The problem with such a rigid classification is that it fails in a number of important ways ... it is neither an accurate description of the number and shape of the morphemes involved in the system, nor of the syntactic behavior of those morphemes ... It is based on an assumption that there is a clear and unerring way to distinguish between case and postpositional morphemes in the language, when in fact there is no clear distinction.

In other words, Tamil being an agglutinative language, you can stick a bunch of different sounds onto the end of a word, each shifting the meaning, and there is no clear way to call some of those sounds "cases" and other sounds "postpositions".

Schiffman asserts that this system of 7-8 cases was originally developed for Sanskrit (the literary language of North Indian civilizations, of similar antiquity to Tamil, and the liturgical language of Vedic Hinduism) but then tacked onto Tamil post-facto, despite the languages being from completely different families with different grammars.

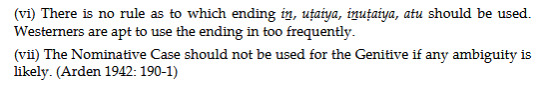

Schiffman goes through a variety of examples of the incoherence of this model, one of my favorites quoted from Arden 1942 again:

There is no rule as to which ending should be used ... Westerners are apt to use the wrong one. There are no rules but you can still break the rules. Make it make sense!!

Instead of sticking to this system of 7-8 cases which fails the slightest scrutiny, Dr. Schiffman instead proposes that we throw out the whole system and consider every single postposition in the language as a potential case ending:

Having made the claim that there is no clear cut distinction between case and postpositions in Tamil except for the criterion of bound vs. unbound morphology, we are forced to examine all the postpositions as possible candidates for membership in the system. Actually this is probably going too far in the other direction ... since then almost any verb in the language can be advanced to candidacy as a postposition. [!!]

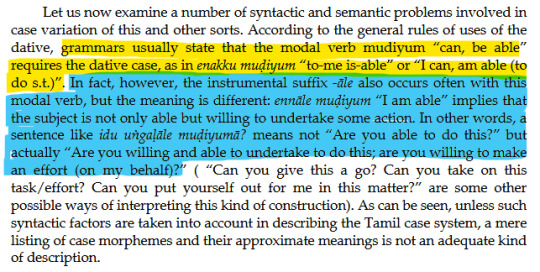

What Schiffman does next is really cool, from a language nerd point of view. He sorts through the various postpositions of the language, and for each area of divergence, uses his understanding of LT and ST to attempt to describe what shades of meaning are being connoted by each suffix. I wouldn't blame you for skipping through this but it is pretty interesting to see him try to figure out the rules behind something that (eg. per Arden 1942) has "no rule".

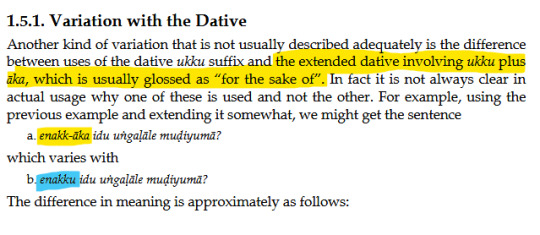

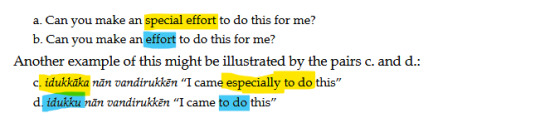

On the "extended dative", which connotates something like "on the behalf of" or "for the sake of":

I especially find his analysis of the suffix -kitte fascinating, because Schiffman uncovers a potential case ending in Spoken Tamil that connotes something about the directness or indirectness of an action, separate from the politeness with which the person is speaking to their interlocutor.

Not to blather on but here's a direct comparison with Finnish, which as stated earlier has 15 cases and not the 7-8 commonly stated of Tamil:

What Schiffman seems to have discovered is that ST, and LT too for that matter, has used existing case endings and in some cases seemingly invented new ones to connote shades of meaning that are lost by the conventional scholar's understanding of Tamil cases. And rather than land on a specific number of cases, he instead says the following, which I find a fascinating concept:

The Tamil Case System is a kind of continuum or polarity, with the “true” case-like morphemes found at one end of the continuum, with less case-like but still bound morphemes next, followed by the commonly recognized postpositions, then finally nominal and verbal expressions that are synonymous with postpositions but not usually recognized as such at the other extreme. This results in a kind of “dendritic” system, with most, but not all, 8 of the basic case nodes capable of being extended in various directions, sometimes overlapping with others, to produce a thicket of branches. The overlap, of course, results from the fact that some postpositions can occur after more than one case, usually with a slight difference in meaning, so that an either-or taxonomy simply does not capture the whole picture.

How many cases does Tamil have? As many as its speakers want, I guess.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gojo x Hindu!Wife!Reader Arranged Marriage

Note: Cold Gojo.

You, a 25 year old Hindu woman, and Satoru were in an arranged marriage since 2 years. He's always cheerful, except when you're around of course. It's clear to everyone that you're not welcome into his life at all. This is why you aren't accepted into Satoru's friend group. Although, the students love you like you're their mother. They're always used to seeing your smile, which is fake of course. You are a very good teacher at Jujutsu high, and our curse technique is being able to bend the laws of physics. You were heading back from your missions at 11:00 PM, like normal, but something was different. You were hit by the cursed technique of the curse you exorcised. You somehow got into the house, but you were bleeding a lot. Satoru was sitting on the couch and chilling, he turned his attention to you, as his eyes widened, he rushed towards you and scooped you up in bridal style. Without a word, he took you to his bedroom and took out the first aid kit. He treated your wounds, and then let you rest in his bed because you fainted. 2 hours later, you finally wake up. Satoru is sitting at the edge of the bed with his head down low, you can hear him sniffling and sobbing...

You: Satoru?

You say as you sit up on bed. Satoru rushes to you, revealing his teary face. He jumps onto the bed and then hugs you tight. You blink for a moment with your eyes widened, but you calm down and hug Satoru back while smiling. Satoru cries onto your breast and hugs you tighter, while you caress his head. It looks like almost losing you taught him your importance...

You: Shhhhhh... It's okay........

You say while comforting Satoru and caressing his head. Satoru says in his breaking voice...

Satoru: Y-y/n..... I'm so s-sorry-y...... I-i should have l-loved yo-ou m-more and understood-d your-r importance-e.... I-i-

Before he can speak more, he bursts out into tears again. After a few hours, he finally calms down. Right now, he is hugging you with his face buried into your breast. You kiss his soft head and say...

You: Now now, stop crying my sukh(Note for reader: Sukh means happiness).

Satoru: W-wh-hat does Sukh mean?

You smile and reply...

You: Happiness in Sanskrit.

Satoru hugs you even tighter and says...

Satoru: E-even after I never l-loved you or c-cared for you, you still call me your h-happiness, why-y?

You: It's because of my dharma. Think of dharma as the code of conduct in Hinduism. Just because somebody considers me their enemy, doesn't mean I do the same thing. If someone does something wrong, I shouldn't repeat that same thing because it's wrong.

Satoru: I'm sorry....... I don't deserve you to be my wife. You're way too good for me.......

You peck him on the forehead and say...

You: I love you Satoru, and don't worry, everyone deserves a second chance. Also, you've proved that you deserve a second chance because you took care of me, forgetting all your hate the moment I needed you. I appreciate it.

**Should I continue this?**

#gojo x fem!reader arranged marriage#Hindu!Reader#arranged marriage#gojo x y/n#gojo x you#gojo satoru#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#gojo x reader#gojo#Indian Reader#Desi Reader

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

tamil is such a language. the pronoun to refer to more than one person ("they" in english) is also the pronoun to refer to someone you respect. the pronoun to refer to a thing ("it" in english) is also the pronoun to refer to children and pets. it's one of, if not the, oldest language. some guy came up with 1,330 couplets of seven words each with complex metaphors and life lessons because why the fuck not. there are two r sounds. there are two l sounds. there are three n sounds. pronouncing a word slightly differently could mean the difference between saying "school" and "lizard". there are several letters that exist but are not used at all. there's a letter that sounds like if you mixed r and l in a blender. it stole letters from sanskrit. it has over two hundred letters. its written version and spoken version could be mistaken for two different languages. it's spoken in the state whose name literally translates to "land of the tamils". it's worshipped like a god . . .

#anyway. who wants to guess my second language#my tamil is so rusty guys. it's not good . . . when i went to india my relatives were highkey taking shots at me#tamil#my language#indian languages#languages#indiablr#story post#<- because informative#stria speaks#the guy is tiruvalluvar btw. i think that's how it's spelled in english. and the couplets are called tirukurals. for googling purposes#also fun fact. the “l” at the end of “tamil” actually is not an l. it's the aforementioned sound that blends r and l#but people that can't speak tamil or some other language with that sound (korean also has it i think) aren't really able to pronounce it#so it's left as an l. but that's technically incorrect

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hundred-Syllable Mantra of Vajrasattva

To meditate on Vajrasattva is the same as to meditate upon all the buddhas. His hundred-syllable mantra is the quintessence of all mantras.

-Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche

Vajrasattva's mantra is a powerful purification prayer that invokes the mindstreams of all the buddhas. Khenpo Sherab Sangpo suggests that his students recite this mantra 21 times or more each day. We have collected various translations to help with your study. Additional resources can be found on Lotsawa House.

Sanskrit with English translation:

Om is the supreme expression of praise.

vajrasattva samayam anupalaya vajrasattva

Vajrasattva, ensure your samaya remains intact.

tvenopatistha droho me bhava Be steadfast in your care of me.

sutosyo me bhava

Grant me unqualified contentment.

suposyo me bhava

Enhance everything that is noble within me.

anurakto me bhava

Look after me.

sarvasiddhim me prayaccha

Grant me all accomplishments,

sarvakarmasu ca me And in everything I do

cittam sreyah kuru

Ensure my mind is virtuous.

hum

The hum syllable is Vajrasattva's wisdom mind.

ha ha ha ha

These represent the four immeasurables, the four empowerments, the four joys, and the four kayās.

hoh

What joy!

bhagavan sarvatathagatavajra

Blessed One, who embodies all the tathagatas, Vajra(sattva),

mã me muñca

Never abandon me!

vajri bhava

Grant me the realization of vajra nature!

mahasamayasattva

Great samayasattva,

ăh

l am one with you.

#vajrasattva#buddha#buddhist#buddhism#dharma#sangha#mahayana#zen#milarepa#tibetan buddhism#thich nhat hanh#Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche#Padmasambhava#Guru Rinpoche#amitaba buddha

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The mind is everything; what you think you become.” – Buddha

The Buddha: A Spiritual Teacher and the Founder of Buddhism

Buddhist Prayers and Rituals

Buddhism is a spiritual tradition that emphasizes the cultivation of wisdom, compassion, and inner peace through various practices such as meditation and ethical conduct. One of the most important aspects of Buddhist practice is the use of prayers and rituals. These practices are used to cultivate a deeper connection with the teachings of Buddha and to develop a deeper understanding of the nature of reality.

Prayers in Buddhism are often recited in order to invoke the blessings of the Buddha, the Dharma (the teachings of Buddha), and the Sangha (the community of practitioners). These prayers may be recited in a traditional language such as Pali or Sanskrit or in the local language. They can also be recited individually or in a group setting.

Rituals in Buddhism are also a common practice. These rituals may include offerings to the Buddha, such as incense, flowers, and food, as well as prostrations, circumambulations, and chanting. These rituals are performed as a way to show respect and gratitude to the Buddha and to invoke his blessings.

In addition to these traditional prayers and rituals, many modern Buddhists also incorporate more contemporary practices into their spiritual life. Some use mindfulness, Qi Gong, yoga or other forms of meditation to deepen their connection with the teachings of Buddha. Others may participate in social or environmental activism as a way to put the principles of Buddhism into action.

Overall, the use of prayers and rituals in Buddhism is an important aspect of the spiritual path. These practices help to connect us to the wisdom and compassion of the Buddha, and to develop a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Bodhidharma and Chan Buddhism (Zen)

Bodhidharma was a monk who is traditionally considered to be the founder of Chan Buddhism, also known as Zen Buddhism. He is said to have been born in India and to have traveled to China during the 5th century CE. He is credited with bringing the teachings of Buddhism to China, and with establishing the first Chan monastery in China.

The teachings of Chan Buddhism, as passed down by Bodhidharma, emphasized meditation and the direct experience of enlightenment, rather than reliance on scriptural study or ritual. The teachings of Bodhidharma and Chan Buddhism would greatly influence the development of Zen Buddhism in Japan and other East Asian countries.

The emphasis on meditation in Chan Buddhism is reflected in the practice of “wall gazing” or “wall contemplation” (Chinese: módao, Japanese: kōan), which is said to have been introduced by Bodhidharma. The practice of wall gazing involves sitting facing a wall for long periods of time, and using that time for deep introspection and contemplation.

The teachings of Chan Buddhism have been passed down through a line of patriarchs, each of whom was considered to be the spiritual heir of Bodhidharma. This line of transmission, which is known as the “mind-to-mind transmission” or “mind-seal transmission,” is considered to be a fundamental aspect of Chan Buddhism.

In summary, Bodhidharma is considered to be the founder of Chan Buddhism, also known as Zen Buddhism. He is credited with bringing Buddhism to China, and with establishing the first Chan monastery in China. His teachings emphasize meditation and the direct experience of enlightenment, and his practice of “wall gazing” or “wall contemplation” continues to be an important aspect of Zen Buddhism today.

Zen Buddha by Talon Abraxas

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

At Vauxhall Gardens, [...] giant paintings were erected in the “Pillared Saloon” of seemingly geographically opposed colonial wars: one painting of The Battle of Plassey (1757), which secured Bengal for the British East India Company, hung next to another symmetrical work that portrayed the British capture of Montreal and, later, Canada itself. That these and other sizable aesthetic works were “designed to be an immersive virtual-reality experience” testifies to Cohen’s larger claim in The Global Indies that 18th-century fashion, rank, sociability, and class were intimately bound up with race and colonialism, particularly through the period’s joint imaginary of the “Indies.”

The Indies describes a shared fantasy - and unquestionable material reality - of wealth accumulation that yoked together the “West” (the Caribbean and North America) and “East” (the Indian subcontinent) Indies in late 18th-century British culture, a conceptual proximity so thorough and unrelenting that its effects reverberate [today] throughout the contemporary [...].

---

The prelude to Ashley L. Cohen’s The Global Indies opens in a pleasure garden - not just any such garden, but the largest and most spectacular of these 18th-century sites of fashionable culture [...]: London’s Vauxhall Garden. At Vauxhall, Londoners who could afford the entrance fee were treated to an array of wonders and excesses. A well-known chapter entitled “Vauxhall” in William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847–’48), for example, finds Jos Sedley, an “indolent” officer of the East India Company recently returned to London, drunk off the garden’s signature "rack punch.” “Everybody had rack punch at Vauxhall,” [...]. Lest a reader mistake punch for a mere artifact of the pleasure garden or a one-off comedic incident, “that bowl of rack punch was the cause of all this history,” the narrator stresses about his unfolding novel. [...] Punch, an alcoholic drink popular with colonial officers of the East India Company, was usually made with a combination of five ingredients including sugar cane and spices, and probably derives from the Sanskrit word “pancha,” meaning five (and invites an etymological link with the Persian panj and with Bengali five-spice mix, panch phoreen). Rack punch’s association with Vauxhall, with India, and with Vanity Fair’s narrative construction was hardly a stretch for Thackeray’s Victorian readers, and probably registered as quite natural, though it carried more than a whiff of the unseemly. But then again, to 18th-century Britons, “natural and a little unseemly” could easily describe the “worldwide empire that stretched from the East to the West Indies” [...].

---

It’s tricky business to think seriously inside of the 18th-century’s analytic tools, but The Global Indies pulls it off, not least because Cohen is appropriately blunt [...], reminding readers of the everyday racism of the Georgians and their fashionable sociability. The book benefits, too, from a rich body of existing work [...] [by] scholars like Edward Said and Srinivaas Aravamudan. [...] [T]he “Indies mentality” enters a critical landscape that has lately taken up the connections between geographically far-flung events in modernity: North American settler colonialism, Atlantic slavery, colonialism in India, and the migration of Chinese and South Asian indentured labor.

Lest these all seem like separate histories that have produced separate discursive notions of race, critics like Lisa Lowe, Jodi Byrd, Tao Leigh Goffe, and now Cohen assure us that they are not, and that our modern ideas about race are intimately shaped by the interconnected and forced movements of Black and brown people across the world. [...]

Cohen spells out how British liberal reformers and abolitionists found a solution to ending West Indian slavery in the continuation of so-called “free” wage labor in Bengal. Sugar produced by Bengali peasants laboring under the threat of starvation came to replace sugar produced on West Indian plantations well into the 19th and 20th centuries. One only has to look up the multiple Bengal famines (1769–1770, and 1943) to calculate its effects. [...]

[T]he architects of the [American transcontinental] railroad “imagined a new era of US hegemony in a mold cast by the imaginative geographies of British imperialism.”

---

All text above by: Ronjaunee Chatterjee. “The Colonial Mentality, Past and Present.” LA Review of Books. 3 September 2021. Published online at: lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-colonial-mentality-past-and-present/ [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#abolition#colonial#imperial#ecology#forests#plantation#tidalectics#archipelagic thinking#global indies#intimacies of four continents#multispecies#plantation afterlives

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

HWS SEA but make it HetaDND

Enjoy these rough sketches because I will literally not come back to them until December. 🥲

(From Back —> Front, L —> R)

VN: Bumped into a couple of Quora answers that discussed archery practice, which got me thinking about Viet as a mounted archer, and I immediately thought of the elephants that the Trung sisters & Ba Trieu rode on. So Ranger: Beastmaster — also what if the elephant was from Thai? 🫣💘 Easily a tank through her mount, but can fight well as a DPS (think OW D.Va). ID: The thing is he has the fighting style of a Warlock(: Genie?) but the character of a Paladin(: Oath of the Ancients). He’s giving CR Fjord. 😭💞 For sure, TANK. TH: He’s just a Monk. Debated on his subclass for a long time because he’s a war freak charge-into-the-frontline kind of fighter. Way of Mercy is ironic but I love the imagery of the Merciful Masks (except he gets the khon styles). Way of Shadow — it’s on one possible etymology of Siam (Sanskrit, “dark”). Easily a DPS type. MY: Druid: Circle of the Moon for the Wild Shape into a Tiger, and as of typing this I just realized the moon motif. Mostly support, but upset him just enough and he’ll easily switch gears. PH: Bard: College of Swords for the two-weapon fighting style aka arnis/kali/eskrima. Personally, he’s more DPS than support, though as a latter Dirge Singer & Siday fit the bill. SG: See, the first thing that came to mind was the RO Alchemist class for the Homonculus feature — hence, his companion Fishball. Obviously there’s Artificer: Alchemist for that, but also it would be cool if Fishball is just a “chibi” form of his patron of a water dragon— Warlock: Fathomless. Not to mention Singa would have both high INT and CHA — alas, he’s a Support guy.

(more notes under the cut)

I jokingly called this AU as Dungeons & Drawing Circles, but truth be told I’m not restricting it to being after DND, let alone 5e. Now I’m just throwing hands and calling it a fantasy RPG AU, although out of familiarity, I do refer to DND 5e often. The classes I highlighted above are just there for where I got the inspiration.

I’ve had the occasional “oooh I think [character] would be a [class/es]” hc over the years, but I ended up expanding on the AU as a means of coping with the early months of ECQ. Now there’s so many plot bunnies that I’d summarize as: your og main 8 unwittingly team up for a quest and, over time, they hit a point where they realize that they cannot fight the BBEG alone (or at least just the 8 of them), so they travel around the world recruiting allies a la Suikoden 108 Stars of Destiny.

It’s even got a literal history timeline where preceding events (and characters!!!) are involved with the BBEG and ultimately why the main 8 came together. Think playing a later game in a series where you not only get to meet the playable characters from earlier games, but you get to recruit them.

And I just wanted to draw cool fantasy looks, haha! Nevertheless, nothing is final — especially when I've clearly taken inspiration from some indigenous groups. It's why I shelved this for so long because I need to do more research and it's just not something I have a lot of free time for.

#hetalia#hws philippines#hws indonesia#hws vietnam#hws thailand#hws malaysia#hws singapore#hws sea#fantasy au#fantasy: hetadnd#no reblog because i hate showing sketches <3#posting here because this is a concept blog after all

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Page 53 from Kalāpustaka (MS Add. 864)

#manuscript#illuminated manuscript#ms add. 864#kalāpustaka#bhagavata purana#mahābhārata#rāmāyana#vetālapañcaviṃśati#jātaka#c: nepalese#y: 1600s#l: sanskrit#t: page

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

languages they've covered so far:

Scots, Akkadian, Old Saxon, Sanskrit, Ossetian, Old English, Estonian, Medieval Latin, Mexican Spanish, Farsi, Lithuanian, Czech, Welsh, Tigrinya, Old Irish, Mari, Bulgarian, Biblical Hebrew, Kashmiri, P'urhépecha, Catalan, Romansh, Marathi, Mansi, Proto Germanic and Burgenland Croatian!

I've shared this podcast before but every time I listen to it I get so delighted by linguists hyping each other up and getting excited talking about their area of interest I feel compelled to share it again skdjfhghj

#scots#akkadian#old saxon#sanskrit#ossetian#old english#estonian#latin#spanish#farsi#lithuanian#czech#cymraeg#tigrinya#gaeilge#old irish#mari#bulgarian#hebrew#kashmiri#p'urhépecha#català#romansh#marathi#mansi#proto germanic#croatian#sr#language resources#l

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Note

if you havent already can u tell stuff about your neo 3s 🥺🤲 i care them

YEAH!!

Both

outside of agent work, they have been part of a delinquent group for quite some time, ever since they were very little! they met through that group and stuck together ever since

the rest of the agents don’t recognize them when they’re dressed in their different clothing! (which looks similar to the deliquent amiibo clothing)

(i’m working on developing that silly little group….)

they found smallfry by picking him up outside of grizzco! they named him Kuz, because he’s like a silly baby cousin

before the NSS, neither knew how to read or write

they got lost in the desert looking for a deliquent friend of theirs who went missing! after some time they stumbled upon cuttlefish and the rest is history lol

i’ve said this like a billion times but Sicily/Cap = mommy?

(do i look l-)

their arms were tainted just from lots of accidents from agent work! it accumulated especially in space, when dodging fuzzballs was especially hard!!

they’re not sure if it’s gonna have any lasting negative effect on them, all that they’ve been able to figure out is that it stings when rinsed with water.

also, they purr and act mammal-like now. i can’t help it T_T

Trikaya

A FERAL CHILD! she’s literally on silly mode maximum ALL THE TIME. if she’s not something is DEATHLY wrong

she loves to put her hair up in pigtails, because she likes subverting expectations!

she’s average at everything! literally everything! it’s kind of astounding how much she can do at a normal level

smallfry’s primary caretaker! she loves to dress him up like a little dolly!

she’s very acrobatic, flexible and agile. she loves to do freaky tricks that give sicily secondhand bone hurting disease.

although she’s very strong willed, she’s still very sensitive…

very gullible, would probably believe you if you said chocolate milk comes from brown cows

literally left in a cardboard box all alone as a baby, wettest little squitten you’d ever see :(

Frye named her! the name means ‘three bodies’ in Sanskrit. before that, it was mostly ‘girl’ or ‘Agent 3’

Mitsuo

very quiet, but also very perceptive and detail oriented. he gets so lost in analyzing some things that sometimes he looks really mad lol

has a lot of anxiety regarding speaking, so he’s a selective mute! he’ll speak if he absolutely HAS to or if he’s really close to someone, but otherwise he speaks SSL (splatlands sign language), a mix of inkling and octoling SL

trikaya translates for him, and often understands what he needs with just a glance!

around strangers he has on a tough attitude, but around the NSS he’s very gentle and curious. he asks a lot of questions

he doesn’t have the most accurate aim as a charger main, but damn if he can’t apply pressure!

trikaya’s big bro!

his parents were octarian army refugees that sent him across the world to the splatlands as an infant to give him a better shot at life. he started off in a foster home but ran away due to mistreatment

sometimes he still wonders if they’re alive

Shiver named him! his name means ‘light/shine’ in japanese, but can also mean ‘third son’ and is sometimes spelt with 三(three).

HOPE YOU LIKE! AND SORRY THIS TOOK SO LONG:)

#please correct me if i’m wrong on the name stuff btw!!#anyway tysm for asking :D#my babiieessess#trikaya(3)#mitsuo(3)#new agent 3#splatoon#splatoon 3#return of the mammalians#splatoon oc#splatoon headcanon#digital art#artists on tumblr#wooden speaks#my art#ask#corn418

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rati

The Hindu Goddess of Love, Lust, Sexual Pleasure, Carnal Desire, Lust, and Passion. Both the Female Counterpart and Wife of Kamadeva "Kama". The Mother of Harsha and Yashas.

She is usually depicted as a Maiden with the Power of Enchanted Love and is usually seen with her Husband in Paintings. She is also known as "Mayavati" when her Husband is Reborn as "Pradyumma". The Name "Rati" comes from a root word, "Ram" or "Sanskrit" meaning either "Joy" or "Delight" (but it's more usually referred to sexual love as she represents the lustful pleasure of Women that does not refer to Motherhood). She also rides a Horse that is very Beautiful as she is and like her Husband, she is associated with Parrots.

After the creation of the 10 Prajapatis, Creation Deity (Brahma) creates Kamadeva from his mind as Kama was given the task to spread love in the world by his own Flower Arrows. When Kama shoot one of his arrows against Brahma and the Prajapatis to fall in love with Brahma's Daughter (Sandhya) which made Shiva laugh so hard but it also embarrassed Brahma and the Prajapatis with tremble and sweat that causes one of the Prajapatis (Daksha) to drip a drop of his sweat (thus, Rati) was born, giving Kama his own Bride/Wife. However, seeing on how Brahma was instantly humiliated by one of Kama's tricks, he cursed him into being turned into Ashes by Shiva until that He and his Wife would soon be Reincarnated.

In a second version of her birth, The Brahma Vaivarta Purana tells that Sandhya took her own life and became Rati when Vishnu resurrects her into Rati and became Kama's wife, after when Bruma lusted Sandhya. Though some versions do keep the Sweat birth thing. However, Another version states that Shiva is Rati's Father.

In the Myth of Rati and Kamadeva's reincarnation, when Shiva's prophecy was said that he was going to have a child in order to stop the Demon (Tarakasura) from destroying the universe, Kama was given the task to make Shiva fall in love with someone to have an Heir. As The Two Love Gods went up to Shiva (who was in his own meditation), Kama took the form of a Breeze and shot Shiva with one of his Arrows which caused Shiva to burn Rati's Beloved Husband into Ashes by his Third Eye which caused Rati to have a mental heartbreak of her Husband's death.

When her Husband was reborn as Pradyumma as the Son of Krishna, the Demon King found out that Rati's Husband was reborn, he threw the Child Pradyumma into the ocean where the Newborn would be swallowed as a fish but when a Couple found Baby Pradyumma under the fish's belly, they decide to raise the Rebirth Kama. Rati then took the form of a Woman under the name, "Mayavati" who would then serve as both a Nanny and later Wife to Pradyumma. After when Pradyumma slayed the Demon King, Kama and Rati return their own previous forms and return back to Dwarka.

SBSP Universe

Rati is very well pleasant, sweet, kind-hearted, a bit sly, and devoted with such desires of love as She and her Husband (Kama) are Partners who help each other out to spread the love throughout the world. Although despite the fact that she does look very seductive compare to Aphrodite and Venus, she can understand others' love for her but she would never cheat on her Beloved Husband. She's also a well caring and gentle Mother to their Sons (Harsha and Yashas).

However, if she saw that one lover turn out to be either abusive or selfish to their own significant other, she would tend to curse the live of a Toxic Partner for being so cruel towards their own partner if one must ever dare to tick her off with Anti-Love. She also happens to have her own Two Pets (A Parrot and even a Mare).

Given on how that Brahma saw that Kama felt so lonely that he desired a consort for himself, Rati was sent by Brahma to meet Kamadeva in a Beautiful Forest. Curious as she was around in the forest searching for him, they accidentality bump into each other and had a warm feeling of Love. Thus, it was Love at first sight for how the Love God admired the Love Goddess' Beauty for Rati seemed as although he started to like him after introducing themselves to each other. Rati seduced Kama with all of her might and beauty as she teased him with such love to get his own attention and then later Wed themselves where they were blessed with Two Sons.

During the day when Kama tricked Shiva into falling in love with Parvati through one of his arrows, Rati was curious on what was going on so she decided to help her Husband out to convince Parvati about Shiva that he's not a bad man and that he can be very a Faithful Loving Husband towards her as Parvati trusted the Two Love Gods as she married Shiva.

Although during the Days of Shiva and Parvati's family, Rati was given the task to become both a Nanny and an Aunt Figure to Shiva and Parvati's Sons (Kartikeya & Ganesha) as she would often tend to spoil the Young Gods. Not only that, she's also like as if she's almost a Mother Figure to everyone who treats her with respect.

She's also BFFs with both Aphrodite and Venus as they do love to chat about things that Goddesses would usually brag about as she's part of the Love Goddess Squad (alongside with Freya and Hathor). She also doesn't mind either King Neptune nor King Poseidon.

SpongeBob SquarePants (c) Stephen Hillenburg Rati (c) Hindu Mythology

8 notes

·

View notes